When does it become too hot to operate a model railroad?

When the thermometer reaches 160 degrees.

So said T.R. Goodwin, superintendent of Death Valley National Monument — and model railroad enthusiast — in that oh-so priceless March 1951 issue of Profitable Hobbies Magazine. (Click to read the large scan.)

But the story doesn’t end there. Well, it probably does for most people; but I’m one of those obsessives, remember? I find one (admittedly amusing) article, and I have to find out more.

(Here’s where I recommend you have a beverage & settle in to read. This 1950’s article about a man and his model train set is better than Mister Rogers’ trolley taking you to the Neighborhood of Make-Believe; Goodwin’s train, said to be the only train for 145 miles — and probably long neglected by now if parts of it even exist — takes you back in time.)

While the heat standard for model railroad use set by Goodwin in 1951 should speak for itself, the official hottest temperature recorded for Death Valley is listed as 134° (in July, 1913, at what is now Furnace Creek Ranch). But, that really doesn’t matter much to me; frankly, when the temp reaches 125, most all of my hobbies would cease — as would my breathing, probably. Anyway, I was now left to research T. R. Goodwin himself.

The short article in Profitable Hobbies Magazine says that “Mr. Goodwin opened Death Valley as a national monument under the jurisdiction of the National Park Service in 1933. Since that time he has watched his barren domain grow rapidly in importance as a tourist attraction.” So I thought there would be a rather large amount of information on Goodwin. But I was wrong.

It’s disappointing to find so little on Goodwin; not just because I’m obsessive, but because from what I can piece together, the man plays important roles in US history. And why shouldn’t he? As Superintendent of The Death Valley National Monument, T.R. Goodwin, was called “Emperor of Death Valley” in Harry Oliver‘s Desert Rat Scrap Book (Packet Three, Pouch Four, 1950, page 3, “The Mail Pouch”), saying, “Though his majesty rules an area larger than some of our states with considerable more power than any Governor, it is whispered that his highness has to swat his own Vinegarones and take his own pet tortoise out for a run.”

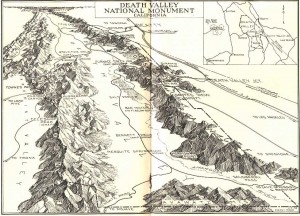

Homey & humorous, yes; full of yesteryear’s non-pc protocol, sure. But knowing that Goodwin was in charge of nearly two million acres, you have to consider the truth of it too.

While the discovery of the Desert Rat Scrap Books (which are full of charming & inappropriate old stories — including many attributed to Goodwin) would be a delightful enough conclusion (or, more accurately, a lovely collection pursuit), there is far more. If you are willing to devote hours, days to researching Goodwin. And I am. (Need to replenish your beverage yet?)

At first the info is sketchy. The “T.R.” in T.R. Goodwin stands for Theodore Raymond Goodwin. He served in the Spanish-American War, lost his first wife after just a few years of marriage, and RootsWeb says that T.R. Goodwin was the brother of noted western artist Philip R. Goodwin.

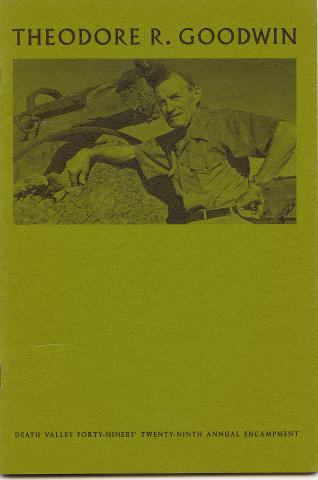

There’s a Death Valley ’49ers “Keepsake” booklet on T.R. Goodwin, published in 1978 — but apparently long out of print. (I’ve ordered a copy & will share what I can.)

Until I get the book, this is what I’ve been able to piece together.

While Goodwin may have been the first official superintendent, his gig didn’t start until 1938, according to the National Park Service. Officially, the Death Valley National Monument was established by President Herbert Hoover on February 11, 1933 and John R. White was the acting superintendent, starting on March 16, 1933, until April 14, 1938; then Goodwin took over on April 15th as the official superintendent.

According to NPS administrative history information, Goodwin seems to have appeared on the government parks scene sometime prior to 1928, when he was the director or roadwork done in the Cold Spring, Anna Spring Plaza, Anna Spring Dam, and the Rim Village area.

Three park roads received surfacing/oil processing treatment in 1928 under the direction of T.R. Goodwin, a road oiling expert loaned to the National Park Service by the California State Highway Commission.

Goodwin must have loved the area & the people, because before he was established as superintendent Goodwin wrote an article (“Park Ranger Believes Early White History Lies Behind Sealed Lips of Red Man Of The Desert,” Inyo Independent, 29 October 1937) on the Indians of the region, “and in so doing attempted to delineate some of the relationships.” He & his writings on Native Americans was written about as well. Perhaps care & concern for the people and land is what got him the superintendent gig rather than his construction skills — or willingness to put up with the heat of Death Valley.

Among the John P. Harrington papers (from 1907 – 1959) held at the Smithsonian Institution, are letters between Harrington, the American linguist and ethnologist who specialized in the native peoples of California, and Goodwin. These letters, dated May of 1946, show Harrington preparing for a field visit to study the Death Valley Indians.

JPH to Goodwin, May 11, 1946:

The writer is Ethnologist in the Bureau of American Ethnology, Smithsonian Institution, and wants to make a study of the Death Valley Indians. I understand that the Indian Village in Death Valley is 30 miles from your Park Headquarters – in which direction and how reached? Is this village at Death Valley Junction? Any information that you give me will be greatly appreciated. It may be that it is too late in the season to visit this Village for I am told that the Indians of it repair to remote places in the mountains during the summer months. I could come in the fall. There must be some Indian who would be a good interpreter or informant – what is the name of such a one, or better the names of several. They say that only the northern part of the Panamint Mountains belonged to the Death Valley Indians, that is, to the Shoshoni Indians, and that the southern part of the Panamint Mountains belonged to the Chemehuevi Indians. That would make it that there are two languages spoken at the Village. Or has the Chemehuevi language retreated – to where? Where was the line? Or was it the Serrano language of the Tehachapi Mountains instead of the Chemehuevi language? Who were the Panamint Indians – did they talk Chemehuevi? Who were the Pitant Indians? Who were the Keits Indians?

Goodwin to JPH, May 15, 1946:

With reference to your letter of May 1[1], 1946…

Most, if not all, the Indians move to the high country in the summer returning after gathering pinon nuts in the early fall. Practically all the males speak good english and one in particular Tom Wilson who is half breed Piute with a Mexican father, is married to the daughter of the former Chief Hungry Bill. Tom is intelligent and speaks excellent english.

I have never heard of any territorial division of the Death Valley Indians. They are supposed to be an off-shoot of the Shoshone tribe. . . . The Death Valley Indians are called Panamint Indians and all live here except for a few around Beatty, Nevada and one family in the Panamint Valley. They are not wards but are under general supervision of the Carson Agency at Stewart, Nevada. All the other Indians I know of surrounding the area are Piutes and said to be tribal enemies of the Panamints.

JPH to Goodwin, May 20, 1946:

Your extraordinarily kind letter, full of information, has arrived and I am surely glad that I wrote you before coming. Several of the matters that you state perplex me.

A Chemehuevi (Piute) Indian told me that the Panamint Indians speak the Piute language; that the northern part of the Panamint Range was held by another kind of Indians, an off-variety of the Shoshones, whom a Panamint Indian can not understand; that way north of these quasi-Shoshones there lives another kind of Piutes known as the Northern Piutes, who speak another non-intelligible language — that same one that is spoken by the Bannock Indians, in southern Oregon, at Carson City, Nev., at Bishop, Calif., etc.

Thanks a million times over for telling me about Mr. Tom Wilson – is he still at Furnace Creek? How could I write to him? He would perhaps instantly know about this Shoshone-Panamint mix-up. Isn’t there any place that one could board at Furnace Creek though the Inn is closed? It may be going to require Indians to straighten this matter out. . . .

Goodwin to JPH, May 27, 1946:

Replying to your letter of May 20, 1946, you apparently have certain information that has never been brought out here, although we have had close touch with the Indians in this vicinity over a period of thirteen years. . . .

While there’s a certain level of condescension in referring to a “half breed” as “intelligent,” one must remember that in 1946 “Injuns” had it far worse. It was a different time & place, and Goodwin was living in The West, among such characters as Walter Scott aka Death Valley Scotty, one of the rough-riders for the Buffalo Bill Wild West Show turned prospectors who built Scotty’s Castle.

Tribute to Goodwin’s own intelligence can be found in history books: He is called “a more sympathetic Park Service official” in Forgotten Tribes: Unrecognized Indians and the Federal Acknowledgment Process by author Mark Edwin Miller, and in Death Valley (Images of America: California), author Robert P. Palazzo says Goodwin was “instrumental in taking up the cause of the Timbisha to prevent their removal from the monument.”

In the correspondence between Goodwin & Harrington, I am particularly amused by the polite perplexed assertions each professional makes as they defend their information about the Timbisha Shoshone people; especially how Goodwin, a former road oiling man turned government administrator, holds his own against Harrington, the bookish linguist and ethnologist.

Gawd – I love old letters like this.

But Goodwin’s story doesn’t end here either.

During World War II Japanese-Americans had it as bad as Native Americans. Not just racist Asian humor, but in removal from their homes. Ten camps on US soil imprisoned over 110,000 Japanese American citizens and resident Japanese aliens during WWII — one of which was Manzanar. A place already with a long history of forced relocated peoples. (I swear my history books & lectures never really imparted this knowledge to me; nor had I ever grasped the concurrent plight of Japanese Americans & Native Americans. And, if that doesn’t blow your mind, consider that Ansel Adams was at Manzanar taking photographs.)

In December 1942, a riot broke out at Manzanar War Relocation Camp. This became known as The Manzanar “Incident.”

On December 6, 1942, one of the most serious civil disturbances to occur at all the relocation centers erupted at Manzanar. Months of internal tension and gang activity had raged between members of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) and many of the first-generation Japanese. Although the JACL leaders acted as representatives to the administration, the elders did not share their views and had little respect for them. Meetings turned into shouting sessions with beatings and death threats against the pro-administration group.

On the night of December 5, six masked men beat JACL leader Fred Tayama while he was in his bed. The leader of the Kitchen Workers Union, Harry Ueno, was arrested for the beating and jailed in the nearby town of Independence despite a lack of conclusive evidence. The next day about 2,000 internees gathered in support of Ueno, and a “committee of five” was selected to negotiate his release. Center Director Ralph Merritt attempted to talk with the agitated crowd and subsequently agreed to bring Ueno back to the relocation center jail to avoid further violence or bloodshed.

…By evening, the soldiers who were stationed in front of the building drew a line in the sand but the hostile protesters surged closer. The crowd became extremely unruly and tear gas was used to break up the demonstration. Although no orders were given to shoot, soldiers fired into the crowd, and a 17- year old was killed and eleven others were wounded. One of the wounded died later on December 11.

Protesters who were considered troublemakers were removed from the camp and held in local jails. Those who were U.S. citizens went to a WRA isolation center at Moab and non-U.S. citizens were sent to Department of Justice camps. Most work, except oil delivery and kitchen crews, was suspended by the administration until after Christmas. By early January 1943, the camp’s operations fully resumed, and schools reopened on January 10.

But what of Tayama & others who were attacked and threatened? Here’s more of the story of Manzanar:

On Sunday night and Monday, December 6 and 7, threats were made against many evacuees at Manzanar who were outspoken pro-American advocates or who were perceived to have pro-WRA administration sentiments. Those threatened included staff members of the Manzanar Free Press, members of the internal security police force, and evacuees who had supervisory jobs in the center. Many of these evacuees, including Tayama, Tanaka, and Slocum, had been active members of the Japanese American Citizens League prior to evacuation, and many had encouraged evacuee cooperation with the government’s relocation policies. John Sinoda, a 25-year-old Kibei who held a key position in the camp’s employment office, was severely beaten by a gang with clubs at the outdoor theater, receiving scalp lacerations. Others were assaulted, including George Kurata, the camp housing coordinator, who managed to escape from his attackers. [49] By Monday noon, approximately 40 evacuees had entered the camp Administration Building, asking for protection and indicating that they were afraid to remain in their barracks. The administration also aided removal from the barracks those evacuees whose names appeared on the dissidents’ blacklists and deathlists. Thus, the number of evacuees taken into protective custody by the camp administration subsequently increased to 65 individuals.

The evacuees in protective custody slept on cots in the Administration Building at night and were crowded into a room in one of the military barracks in the military police compound south of the camp during the day. There was insufficient room for all of them, however, and they were forced to take turns “in getting warm.” They were fed in the kitchen in the military police compound. [50]

Faced with the dilemma of protecting the 65 people, Merritt and his staff immediately began a search for a place outside of Manzanar to house them on a temporary basis. Merritt and Brown had been associated with T. R. Goodwin, Superintendent of Death Valley National Monument, during their days with the Inyo-Mono Associates as well as the Citizens Committee established by the military to ease public relations for the camp with the Owens Valley residents following evacuation. Thus, Merritt sent Brown to Death Valley to inquire as to whether the national monument had any place to house the people. Goodwin offered the abandoned Cow Creek Civilian Conservation Camp, comprised of 16 deteriorating buildings adjacent to the monument’s headquarters. After considerable discussion and clearance was received from WRA Director Myer and General DeWitt, the 65 evacuees, who became known as “refugees,” were sent to Cow Creek on December 10.

…The Cow Creek camp was administered by Camp Director Albert Chamberlain, a WRA employee, and Fred Tayama was elected unofficial “mayor” by the refugees. The WRA staff, evacuees, and soldiers shared the same latrines and showers and ate at the same times in the mess hall which was supplied from Manzanar. After improving their quarters and the grounds of the camp, the evacuee men, needing something to do with their time and appreciative of the hospitality shown by the National Park Service, painted signs, cleaned out springs, built dams, dug ditches, mixed cement, installed radio antennas, and conducted other odd jobs in the national monument without pay. The evacuee women spent their days, caring for their children, assisting in the mess hall, and housekeeping. During their stay. Park Service personnel, as well as the soldiers, took groups of evacuees sightseeing in the national monument and on trips to pick up supplies and mail. The camp had a swimming pool that was enjoyed by the older children. The 65 evacuees remained at the Cow Creek camp under military guard, primarily for their protection, until arrangements could be made for their release through indefinite leave and assistance could be provided for relocation. The American Friends Service Committee played a major role in obtaining jobs and homes for the evacuees, sending representatives to Cow Creek to interview and assist them in planning for relocation. As a result of this organization’s efforts, many of the evacuees relocated to Chicago where the Friends had established a hostel to help those relocating from the relocation centers. As jobs and housing became available, departing evacuees were taken to Las Vegas, the nearest railhead, via military escort. By mid-February the “refugee” camp at Cow Creek was vacated. [51]

I wonder if any of the group of 65 Japanese and Japanese American internees brought into Death Valley for their safety got to see or play with Goodwin’s model railroad?

Is this the end of Goodwin’s story?

It is unclear. For while little else could be found about him, it seems unlikely that such an active man would just wither away, content to be a relic of the past. He must have been more than just a fascinating old coot, with lots of stories to share (should anyone be willing). But for now, I have nothing but blanks.

T. R. Goodwin died in 1972; this I learned from his wife Neva’s obituary, which also lists Mr. Goodwin as “an engineer in Sequoia” prior to placement as superintendent of the Death Valley National Monument. This may not be so accurate. Other research, again tied to Neva Goodwin’s death, states that T.R. Goodwin died in 1969:

T. R. “Ray” Goodwin preceded her in death Oct. 27, 1969. Research Note: Stone reads that he died Oct 25, 1969.

It’s interesting to note that while Mr. Goodwin was an amazing man — one I think ought to be remembered — that his wife’s obit mentions next to nothing of her own life. This sexist fact is noted by Cathy Spude in her discussion of Mrs. Goodwin’s obituary, as published in The Electric Courier, and electronic newsletter for the employees of the National Park Service:

September 11, 1996 Volume 2, Number 13

“Neva Goodwin, 100, died August 14 at the home of her daughter, Kay Hamblin, in Yreka, California. She was buried in Monett, Missouri. Mrs. Goodwin was the first superintendent’s wife to live in Death Valley. T.R. Goodwin had been an engineer in Sequoia when he was put in charge of the newly created monument in 1933. He also served in Yellowstone, Yosemite and Grand Canyon during his NPS career. He died in 1972. Memorial donations in Mrs. Goodwin’s name may be made to Waldensen Presbyterian Church in Monett, MO 65708. Survivors include sister Chris Driskill, daughter Kay Hamblin, son Ted Goodwin, five grandchildren and one great-grandchild. Contacts with the family may be made through the Death Valley public affairs office.”

So we see that gender-based stereotypes in obituaries is not confined to the late 19th and early 20th centuries; it is here in 1996! It appears, from this obituary, that Neva Goodwin’s primary contribution to society was through her roles as wife, sister and mother. More information was given about what her husband did in his career than about Neva in her career as wife and mother.

The editor of this newsletter would probably be defensive if I suggested that his obituary was androcentric; he would no doubt reply that the readers of the newsletter are more interested in fellow employees (i.e., the deceased’s husband) than in their spouses. I wonder how many people in the service do indeed remember a man who died in 1972 (my 21-year career post-dates that event). Neva without a doubt continued to contribute to something at Death Valley, that the public affairs office is handling contacts with the family. What that contribution was, we cannot tell from this obit.

Surely as his wife, living with him in Death Valley, Neva Goodwin had her own work — and stories as well. She must have raised their son (the very one, according to the original 1951 article, the first of T.R.’s toy trains was purchased for). And, I imagine, Neva spend many a night trying to get Superintendent Goodwin to stop playing with his toy trains long enough to get something to eat & sleep before he began he’d have to get up in the morning and become Emperor of Death Valley again.

3 Comments