The popularity of gloves is said to have begun in the 16th century when Catherine de Médicis, queen consort of Henry II of France, jealous of well-dressed men whose wardrobes included gloves, began a campaign to make them part of ladies’ fashion. Catherine’s powers were noted in many areas, including fashion; not only did she succeed in making gloves popular, but after it was discovered that both she and the recently deceased Jeanne d’Albret shared the same glove supplier and perfumier, it was rumored that Catherine had killed Jeanne via poisoned gloves (an autopsy revealed otherwise, but it says something of Catherine — and the popularity of gloves; this story is included in Alexandre Dumas’s 1845 novel of the French Renaissance, La Reine Margot).

By the mid-nineteenth century gloves were de rigueur, making it more than unseemly for a woman to leave the house without wearing gloves — but out-right indecent. Heck, a proper lady wouldn’t be seen barehanded even indoors.

Antique Personal Possessions quotes this letter to The Queen from 1862:

In every costume but the most extreme neglige a lady cannot be said to be dressed except she is nicely and completely gloved; and this applies equally to morning, afternoon, dinner, and evening dress.

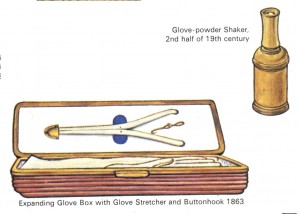

Of course it was also unladylike to wear soiled gloves. Glove cleaners were sometimes used (by cheating cheapskates), but as kidskin (and doeskin) gloves were preferred, most cleaning products failed to clean or effectively hide marks on leather. So gloves were purchased by the dozens and stored in the essential glove box.

Along with gloves themselves and a scented sachet to perfume the gloves, glove boxes held materials essential for putting gloves on: glove stretcher, glove button-hook, and glove-powder shaker.

Along with gloves themselves and a scented sachet to perfume the gloves, glove boxes held materials essential for putting gloves on: glove stretcher, glove button-hook, and glove-powder shaker.

These glove-powderers contained glove powders which not only were to aid in the easing on of tight gloves, but which were often sold as softening and bleaching the hands. Can you imagine what ingredients these powders had? Lead was an incredibly common ingredient in powders and cosmetics of all sorts — how rapidly such chemicals would adhere to and be absorbed by warm moist hands. Obviously Catherine de Médicis needn’t have added anything unusual to Jeanne d’Albret’s gloves if she wanted her dead; but by the same token, Catherine was slowly killing herself as well.

The wearing of gloves, of course, was yet another social rule which distinguished between the working class and the wealthy. Wearing pretty light-colored gloves kept pretty light-colored hands easily discernible from tanned working hands; making the wearing of gloves vital for those with (or seeking) social standing.

The wealthy not only could afford the gloves but the leisure time to wear them — even if wearing gloves kept their hands nearly as useless as if kept in handcuffs.

Certainly this glove-wearing business was far more debilitating than corsets. Which is why I’ve always rather viewed antique glove boxes as little coffins.