Normally, we see the pin-up version of women working in WWII. Like this image of dancers at London’s Windmill Theatre practicing their routine while wearing gas masks and hard-hats with their costumes. (January, 1940.) Or we find articles focusing more on the figures of women, in service or not.

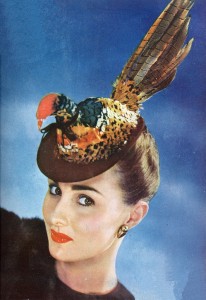

But hard hats were more than de rigueur for cute images of women on the homefront during those war years. In fact, there were many promotional campaigns advising women on how to dress for their new world of physical labor and factory work. This one didn’t emphasize hard hats; but clearly the focus is safely, not being fashionable.

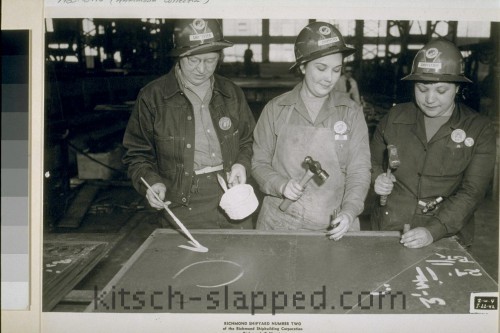

Here’s another image from the Henry J. Kaiser Pictorial Collection showing female employes working at the Richmond Shipyard wearing their hardhats.

Here’s another bit of history:

Mrs. Arlene Corbin (right), time checker in a Richmond, California shipyard brings two-and-a-half-year-old Arlene to a nursery school every morning before going home to sleep. Mrs. Corbin works on the midnight to 7:30 a.m. shift and relies upon the school to keep her daughter busy and happy during the day.

If you collect actual historical objects of women from WWII, check out this vintage wartime fiberglass safety hat.

The hardhat belonged to a female employee who worked for Kaiser Steel in Fontana, CA during 1942-45. It may be more difficult to appear beautiful in a hardhat (even Rosie the Riveter’s bandana is pretty rockin’), but hard hats were the realities in hard times like war. And hats like this are a part of women’s history that shouldn’t be shunned for the pretty pinup version.