I just uploaded these kitschy retro nuns on playing cards to the Zazzle shop I run with friends. Today’s the last day to save 50% with code MAGICALSALES at checkout.

Tag: nuns

Pro-Nun-ciation

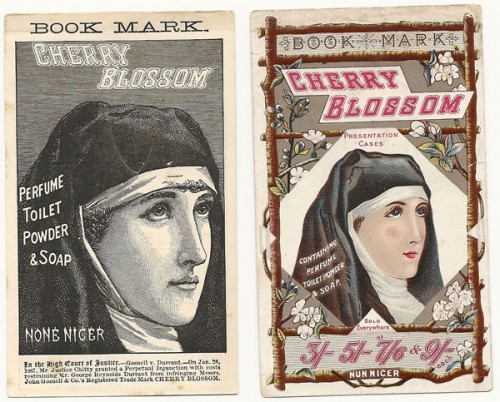

In Look for the Detail!, Beryl Kenyon de Pascual tells the story of this pair of vintage bookmarks:

The fourth example is also from the late nineteenth century. The cosmetic firm of Cherry Blossom—not to be confused with the company that makes shoe polish—produced a bookmark featuring a nun on one side and a biennial calendar on the reverse. The earliest examples were printed in black and white and include the phrase ‘none nicer’, as in the reproduction of my 1889/1890 bookmark. I found the relevance of the nun puzzling in the context until I acquired a chromolithographic issue from 1897-1898. The latter is more decorative and does not have the die-cut page clip found in the black and white series. The nun was nevertheless retained as the central feature. The phrase ‘none nicer’, however, was amended to ‘nun nicer’. The light dawned on me. In some regions ‘none’ is pronounced the same way as ‘nun’. Since I pronounce the two words differently the play on words had passed me by. Possibly other people were puzzled at that time and this may account for the change in the spelling of the phrase to a form that highlights the pun and explains the apparent incongruity of the nun.

I had to read this twice in order to comprehend that there’s another way to pronounce “none” — a way that doesn’t sound like “nun.” Beryl Kenyon de Pascual was born in England — and she worked as an international linguist, so I’m terribly surprised. But even more curious to hear how she and others pronounce “none.” Please do share!

You Can’t Judge A Racist Nun By Her Habit, Part Three (Or, The Little Chink In Sister’s Armor)

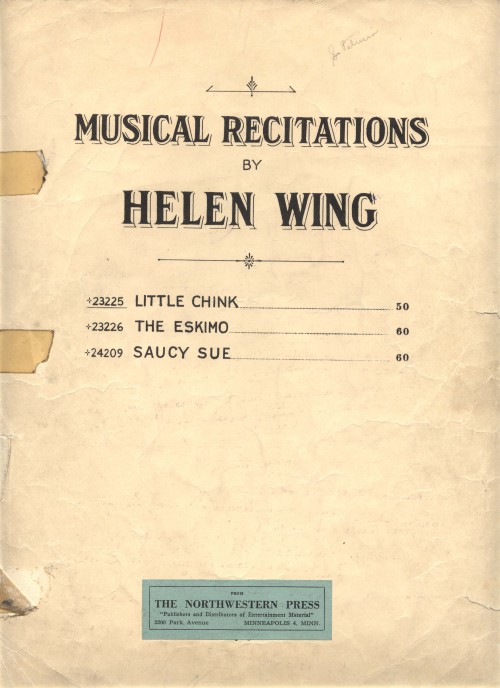

That darn Sister Patricia also owned a copy of Little Chink, one of (at least) three Musical Recitations by Helen Wing.

Little Chink is by one Mildred Merryman — who, as it turns out, is quickly becoming an obsession. More on that in a bit; first, here’s the lyrics.

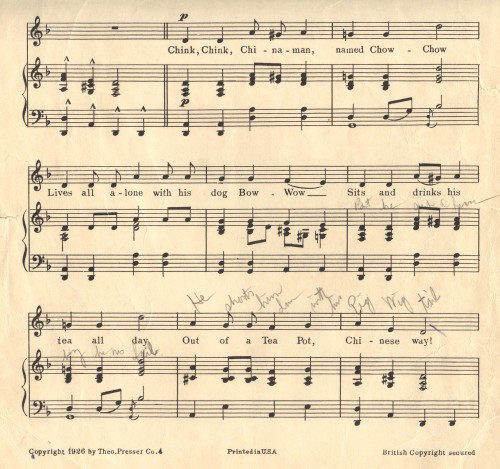

Chink, Chink, Chinaman, named Chow-Chow,

Lives all alone with his dog Bow-Wow,

Sits and drinks his tea all day

Out of a tea-pot, Chinese way.

Chinese girl thinks he’s just right

She sings to him with all her might:Little Chink Chink Chink

I think think think

You must be wise

Little Chink Chink Chink

When you wink wink wink

With your funny little beady, little eyes.

Little Chink Chink Chink, I love-a, love-a you

Lets you marry me and I’ll marry you,

Little Chink Chink Chink

What do you think-What Do you think?

I saw you wink! Little Chink.

I get that the word “Chink” lends itself to easy rhymes like “wink” and “think”, but geeze.

Now, the second verse is not printed with the actual music composition, so when I saw Sister’s penciled lyrics, I immediately thought that she herself had (as she had done with Japanese Love Song) made her own lyrics, creating the “pig-wig tail” part.

But inside the front cover, the entire lyrics are printed. Here’s the second verse:

Once came a big bear Woof! Run, run!

Poor little Chink, Chink have no gun,

But he such a brave boy, He no fail!

He shoots him down with his pig-wig tail

Chinese girl thinks he’s so smart

She sing to him with all her heart.

So while Sister is guilty of purchasing, playing & likely directing a choir of children to sing this song based on the titular ethnic slur, she is free of the sin of writing any part of it. That honor goes to Mildred Merryman…

Mildred Merryman is Mildred Plew Merryman, nee Mildred Plew Meigs. Very little is known about Mildred — something that only makes me more obsessed. I do know that she wrote a number of poems for children, so silly & full of rhyme that they naturally lend themselves to children’s songs — making each poem a potential ditty. (In some cases, a real doozy of a ditty.)

From what I can see, neither her other poems or ditties are so offensive. In fact, they are quite cute. So I continue to hunt for more and am doing some heavy research. Stay tunned for more on Mildred.

You Can’t Judge A Racist Nun By Her Habit, Part Two

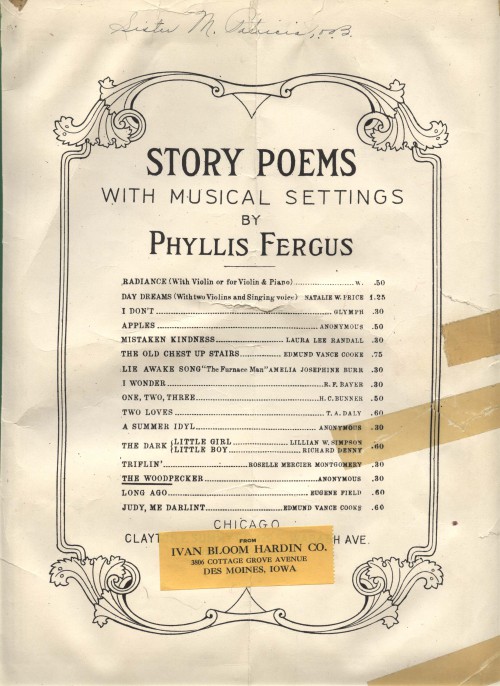

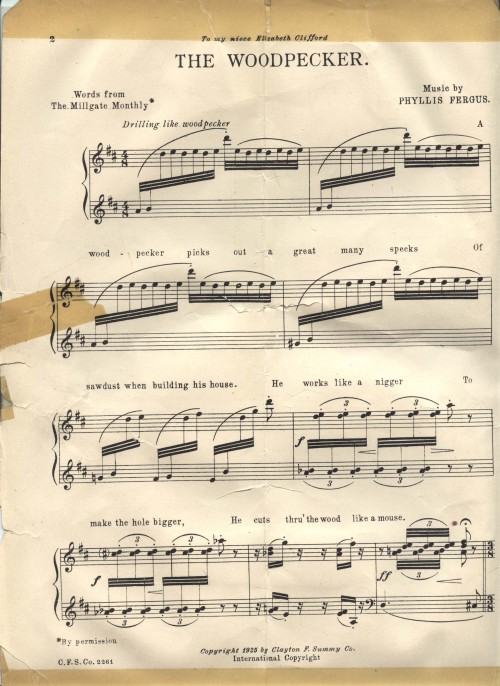

More vintage sheet music owned by Sister Patricia; this time, Story Poems with Musical Settings by Phyllis Fergus.

The song, The Woodpecker (copyright 1925 by Clayton F. Summy Co.), takes its lyrics from an anonymous poem previously published in The Millgate Monthly, and is dedicated to Fergus’ niece, Elizabeth Clifford. Something which likely makes poor Elizabeth cringe — roll over in her grave? — why couldn’t her aunt just pat her on the head and exclaim, “My haven’t you grown!” and give her an ugly frock like the rest of the relatives? Because this is one racist little song:

The Woodpecker

A woodpecker picks out a great many specks

Of sawdust when building his house.

He works like a nigger

To make the hole bigger,

He cuts thru’ the wood like a mouse.

He doesn’t bother with plans of cheap artisans,

But there’s one thing can rightly be said;

The whole excavation has this explanation

He builds it

By working, Well! by using his head!

Can’t you just imagine a classroom full of students with bright shining faces who, at the urging of Sister M. Patricia, are happily singing the n-word as part of their religious dedication?

Singing their way into heaven? Hmmm, more like sinning their way to hell.

Ah, but it was the times… The roaring, racist 20’s.

But if the image of a nun leading a choir of earthly angels in singing the n-word doesn’t illustrate how entrenched and insidious racism is, then what will?

If the name Clayton F. Summy sounds vaguely familiar, it likely is due to the Happy Birthday hullabaloo. (See also: Google Answers.) Which means that the same folks who claim to own the rights to Happy Birthday likely also own this racist little ditty.

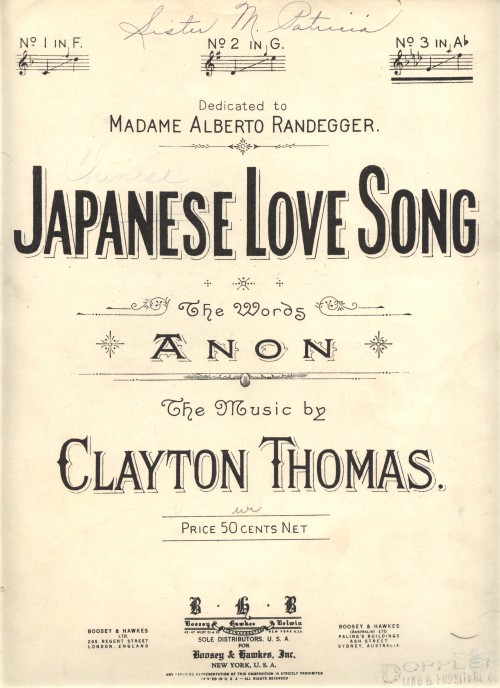

You Can’t Judge A Racist Nun By Her Habit

Normally the most interesting thing to me about vintage sheet music is the cover art; this is because I’m musically illiterate and can’t use it for anything but decoration and/or parts for altered arts (honestly, the only way I am able to carry a tune is to buy sheet music *ba dum dum* ). But this weekend I bought hundreds of sheets of vintage sheet music & some of the most fascinating ones were those that had little to no artwork at all.

All of the pieces I’m showing you today were owned by one Sister M. Patricia, O.S.B. (Order of Saint Benedict), from Sacred Heart Convent, East Grand Forks, Minnesota. (Puzzling then, that at least The Naughty Little Clock Song sheet music would come all the way from Boston! Surely there was a cheaper option in the Twin Cities?)

But anyway, Sister M. Patricia was a racist nun — and I can say that based on her musical habits.

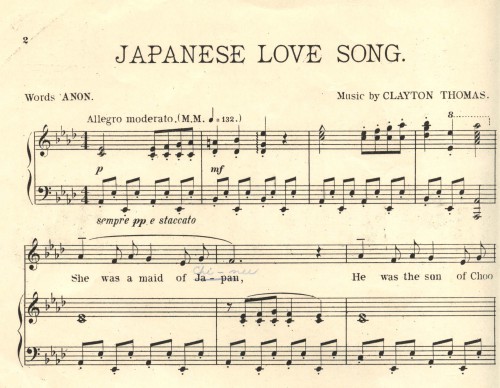

First up, her copy of Japanese Love Song, copyright 1900, words by “Anon”, music by Clayton Thomas aka Salome Thomas Cade aka Nellie Salome Thomas, and dedicated to Madame Alberto Randegger. Only Sister has crossed-out “Japanese” and replaced it with “Chinese” —

Because apparently one Asian is as good, or as heathen, as another. Hey, I’m not calling anyone a heathen! The original lyrics read:

She was a maid of Japan

He was the son of Choo Lee

She had a comb and a fan,

And he had two chests of tea.She wore a gown picturesque,

While he had a wonderful queue,

Her features were not statuesque,

Which matter’d but little to Choo, to Choo,

Which matter’d but little to Choo.He smiled at her over the way,

She coquetted at him with her fan;

“I mally you,–see?” we would say

To this queer little maid of Japan.And day after day she would pose

To attract him, her little Choo Lee,

All daintily tipp’d on her toes,

This love of a heathen Chi-nee, Chi-nee

This love of a heathen Chi-nee.But Fate was unkind to them, quite,

For he never could reach her, you see,

Though she always was there in his sight,

And she look’d all the day on Choo Lee;For a man mayn’t do more than he can,

Tho’ a maiden may languishing be,

When she is a maid on a fan,

And he’s on a package of tea, of tea,

And he’s on a package of tea, ah!

Her revisions also include changing lyrics in the newly created Chinese Love Song:

For continuity purposes, of course, “Japan” was changed to “Chi-nee”. And Sister is nothing if not consistent in her racism, as we’ll see in part two. (Yup, that’s a tease to come back soon.)

PS This little song was performed at a The New York Times, August 31, 1902: