In the last war, women came to look less womanly as time went on, In this war, corsets have established themselves early. A token that feminine lines are to be preserved. Or even accentuated.

According to Mr. James Laver, war should cause women to discard their corsets and cut off their curls. That was the way it worked out in the last war. But that was twenty years ago. Whatever else has been lost or gained since then in Europe, women, at least, have gained — they have gained appreciable figures. Gone are the boyish contours of the ’20’s. The modern woman is as feminine as she has ever been in history, and she goes not propose to allow war to deprive her of her figure at this stage. She’s too well trained in figure-culture. She takes her figure seriously, trains it, exercises it, diets it. soothes it with delicate creams and lotions, and corsets it.

The War Office, also, holds a watching brief for the modern woman’s figure. And well it may, since so many women have enrolled for service in the A.T.S., the W.A.A.F., the A.F.S., and the W.R.N.S. “These women,” said the War Office, “must be corseted, and corseted correctly.” They therefore applied to British corset manufacturer Frederick R. Berlei for designs that would preserve the feminine line, and at the same time be practical under a uniform. The problem was to design a style that would control without restricting. It was solved by eliminating bones, and working solely with elastic materials, firm lace and net, satin and baste on the principal of “directional control” — that is, the line and cut of the garment itself gives sufficient control.

But there was more to it than that. A woman commandant pointed out that girls in the Forces can carry no handbag, nor do they feel it safe to carry valuables in their tunic pockets. Often they doff their jackets to do a job. So, taking a hint from grandmother’s corset, one of the features of the new styles is a pocket tucked inside the girdle waist. If you see a member of the A.T.S. discreetly unbuttoning her tunic, you will know that she’s only getting her bus fare from her corset pocket.

For the A.F.S. and ambulance girl, there’s a special design. It’s a pantee-girdle of elastic and satin, with zip fastening, intended for wear under slacks. It gives perfect freedom of movement and — especially important for the ambulance driver — supports against the danger of those spreading hips that may come from long hours of sitting.

So much for the practical side of these new corsets. What of the artistic? Are they feminine? Certainly. Mostly, these garments are two-piece affairs, girdle and brassiere. They are built on the latest lines to give a slight waist, uplifted bust and controlled torso.

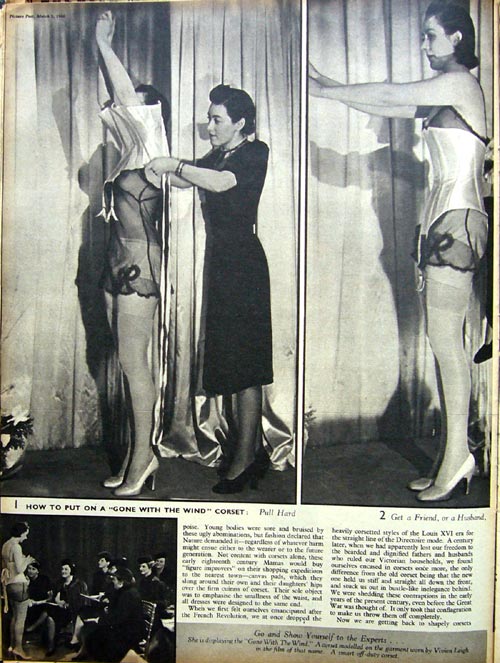

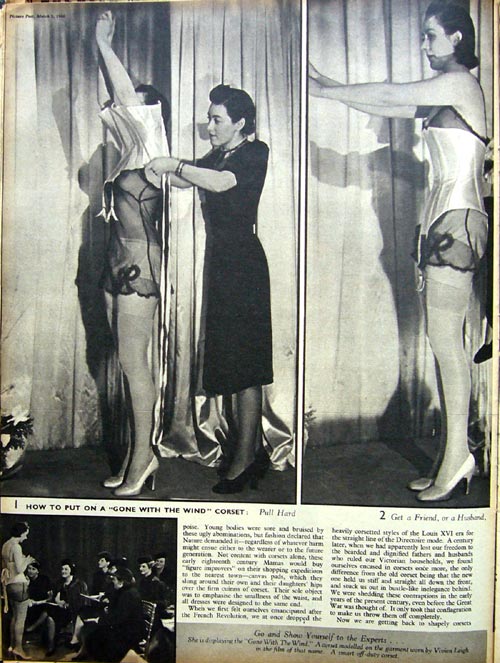

Consider, moreover, that corsets designed for off-duty hours or for civilian women. When you are given a day’s leave and get into an evening frock, long and sweeping and off-the-shoulder, you’ll be wearing underneath it an odd little corset that might just as well have been worn by your grandmother at her fist ball. It will be made of taffeta and will be boned and laced. It will give you a 22-inch waist and pronounced bust and hips. According to the designer F.R. Berlei, it’s called “Gone With The Wind,” modeled on the garment worn by Vivien Leigh in the film of that name. You won’t be able to get into it yourself, so, if you can’t afford a lady’s maid — and in price these corsets are intended just as much for those of us who can’t — borrow five minutes from a friend or your husband can lace you up.

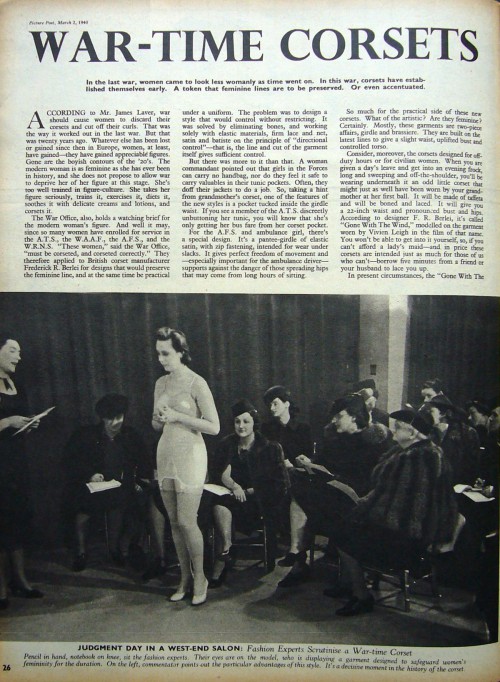

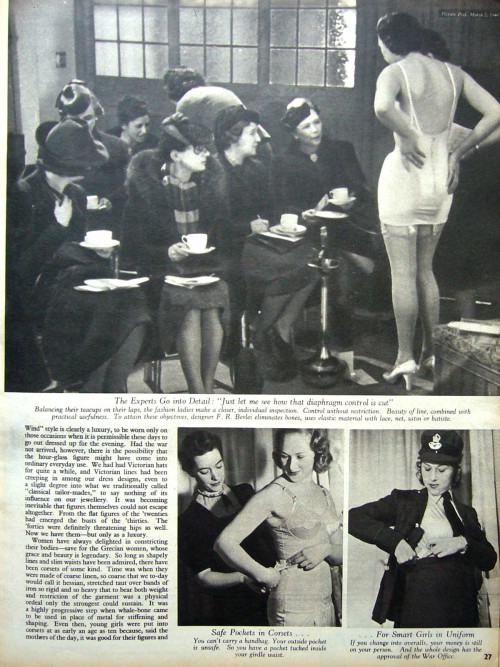

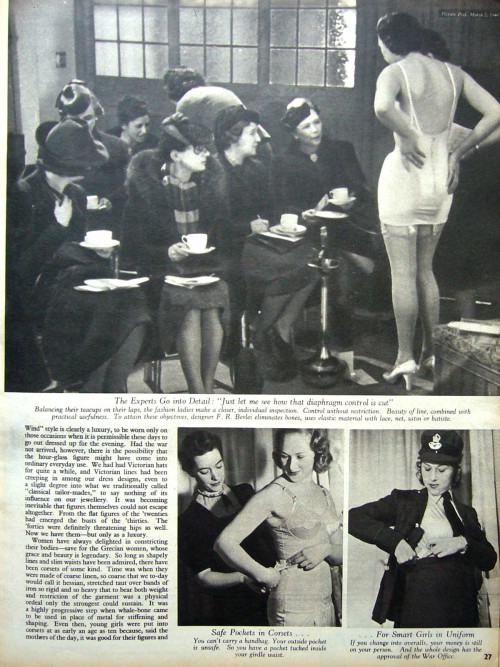

[Bottom Caption: JUDGEMENT DAY IN A WEST-END SALON: Fashion Experts Scrutinise a War-time Corset

Pencil in hand, notebook on knee, sit the fashion experts. Their eyes on the model, who is displaying a garment designed to safeguard women’s femininity for the duration. On the left, commentator points out the particular advantages of this style. It’s a decisive moment in the history of the corset.]

[Caption: The Experts Go into Detail: “Just let me see how that diaphragm control is cut”Balancing their teacups on their laps, the fashion ladies make a closer, individual inspection. Control without restriction. Beauty of line, combined with practical usefulness. To attain these objectives, designer F.R. Berlei eliminates bones, uses elastic material with lace, net, satin or baste.]

In present circumstances, the “Gone With The Wind” style is clearly a luxury, to be worn only on those occasions when it is permissible these days to go dressed up for the evening. Had the war not arrived, however, there is the possibility that the hour-glass figure might have come into ordinary everyday use. We had had Victorian hats for quite awhile, and Victorian lines had been creeping in among our dress designs, even to a slight degree into what we traditionally called “classical tailor-mades,” to say nothing of its influence on our jewelry. It was becoming inevitable that figures themselves could not escape altogether. From the flat figures of the ‘twenties had emerged the busts of the ‘thirties. The ‘forties were definitely threatening hips as well. Now we have them — but only as a luxury.

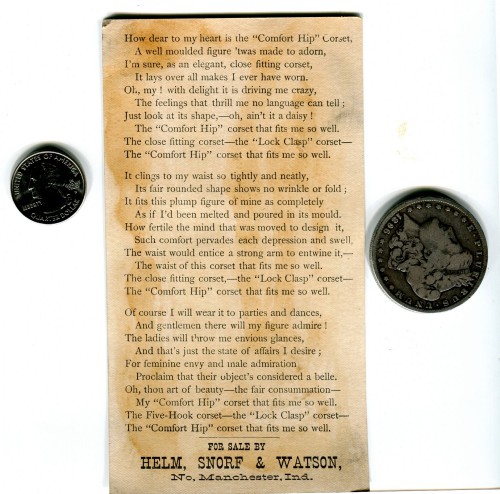

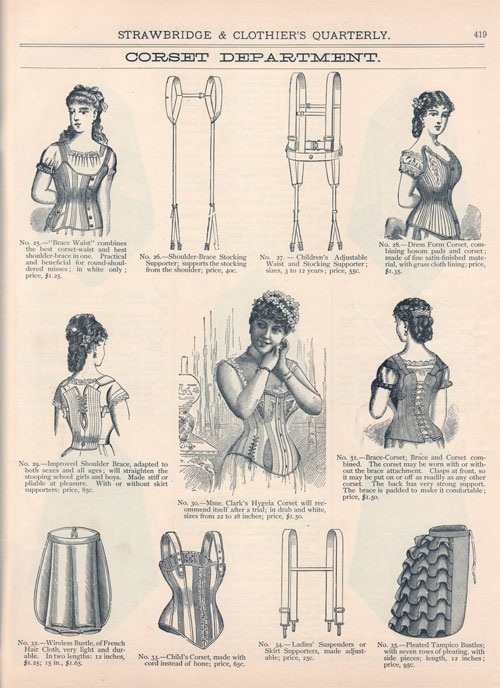

Women have always delighted in constricting their bodies — save for the Grecian women, whose grace and beauty is legendary. So long as shapely lines and slim waists have been admired, there have been corsets of some kind. Time was when they were made of coarse linen, so coarse that we to-day would call it hessian, stretched taut over bands of iron so rigid and so heavy that to bear both weight and restriction of the garment was a physical ordeal only the

strongest could sustain. It was a highly progressive step when whale-bone came to be used in place of metal for stiffening and shaping. Even then, young girls were put into corsets at as early an age as ten because, said the mothers of the day, it was good for their figures and poise.

[Bottom Captions: Safe Pockets in Corsets…

You can’t carry a handbag. Your outside pocket is unsafe. So you have a pocket tucked inside your girdle waist.

…For Smart Girls In Uniform

If you change into overalls, your money is still on your person. And the whole design has the approval of the War Office.]

[Photo Captions: 1 How To Put On A “Gone With The Wind” Corset: Pull Hard 2 Get a Friend, or a Husband, or a Dresser to Tighten You Up… 3 …And Thank Your Lucky Stars That You’re In!

Go and Show Yourself to the Experts…

She is displaying the “Gone With The Wind,” A corset modeled on the garment worn by Vivian Leigh in the film of that name. A smart off-duty corset.

…And See What “Vogue” Thinks

Miss Penrose, editor of “Vogue” (right) and her colleague, Mrs. Pidoux, reserve judgement on the effect that the war has had on corsets.]

Young bodies were sore and bruised by these ugly abominations, but fashion declared that Nature demanded it — regardless of whatever harm might come either to the wearer or to the future generation. Not content with corsets alone, these early eighteenth century Mammas would buy “figure improvers” on their shopping expedition to the nearest town — canvas pads, which they slung around their own and their daughters’ hips over the firm [?] of corset. The sole object was to emphasise the smallness of the waist and all dresses were designed to the same end.

When we first felt ourselves emancipated after the French Revolution, we at once dropped the heavily corseted styles of the Louis XVI era for the straight line of the Directorie mode. A century later, when we had apparently lost our freedom to the bearded and dignified fathers and husbands who ruled our Victorian households, we found ourselves encased in corsets once more, the only difference from the old corset being that the new one held us stiff and straight all down the front and stuck us out in bustle-like indulgence behind. We were shedding these contraptions in the early years of the present century,

even before the Great War was thought of. It only took the conflagration to make us throw them off completely.

Now we are getting back to shapely corsets again. Are we, therefore, less emancipated? Not a bit. But this time, after all our experience throughout history, we are trying to combine feminine freedom and feminine beauty. We are trying to be practical and artistic. That is the point of our latest corset styles. It won’t be long before they are on sale in the shops. They have already been displayed at a private showing for London’s fashion experts. In a graceful West End salon, these well-dressed women gathered in an atmosphere of warmth and perfume. Clad in fox and ermine, they arrayed themselves on spindly gilt chairs and settled to an afternoon’s concentration of “figure foundations,” as many of them prefer to call corsets. A commentator described each model, pointing out its special features. The mannequin paraded between the chairs, stopping here and there to answer spectators’ questions. For an hour, the study continued, till there wasn’t a question unanswered, and the fashion experts’ notebooks were full. It had been an afternoon of work for these women. Even when the hosts served tea, a few had still not finished inspecting and questioning. But others, for the moment regardless of figures, indulged like schoolgirls in chocolate cake. The fashion experts liked these new corsets. So will you. So will the people who see you wearing them.